Processing a bereavement

I often think the experience of being a parent of a child with differences is like being on an emotional roller coaster. It starts with the elation of a newborn baby and at some point later down the line the highs and lows start to appear.

A topic that has come up in conversation frequently recently is bereavement. Bereavement is commonly associated with the death of a loved one, and across the world and throughout societies have we’ve experienced that in spades over the last 15 months.

And I believe, in the same way that it is possible to experience intense pain, without physically hurting oneself, I believe it’s possible to suffer a bereavement without experiencing a death.

I first experienced this myself around a decade ago. At the time our eldest son was struggling at school and didn’t seem to be at all happy. We took him to see an educational psychologist see if we could better understand what was going on.

I remember vividly the day I received the report. I was away from home and staying in a hotel in Coventry for work. I’d completed one of three days at a client’s site and had returned back to the hotel for the evening. I opened the email and started to read. Within the first few pages, the report described my son’s ‘exceptional cognitive ability’. And then as it went on it started to suggest that he may have Dyslexia. The extent of his difficulties was laid bare in black and white.

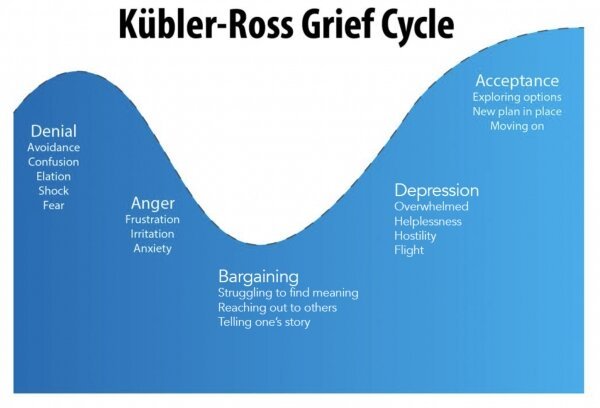

I was devastated. I remember spending most of the evening in tears. Whilst his ability was a revelation, the idea that he was going to struggle to demonstrate that ability and would always be hampered by dyslexia was too much for me to bear. There is no doubt it felt like a bereavement and the grief cycle was in full swing. The grief cycle first described by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross describes the five stages we commonly go through after a bereavement.

Stage one is Denial. When faced with the suspicion that all is not well in the world for our children, we often start here. We’d rather deny what is staring us in the face than acknowledge there is a difference to be better understood. That way, we can, in our own little way, perpetuate the hopes and dreams we have for our child in full denial of reality. It’s a way of clinging on to a sense of ‘normal’, whatever normal is for us. I’ve heard countless stories of parents who confess to living in denial, sometimes for quite long periods of time. I know I was so shocked by my son’s suggested diagnosis there was a part of me that wanted to deny it.

Then comes Anger. We are angry at how our child’s opportunities are going to be curtailed, reduced or different from what we had imagined for them. I know this is where my head was in that Coventry hotel room. I was so angry that he was going to have to struggle to overcome his dyslexia and would struggle to show the world how capable he really was. It was so unfair – or so I told myself.

Stage three is Bargaining. In an effort to avoid dealing with the grief, you find yourself wondering what if. Perhaps if you hadn’t eaten x during pregnancy, or if you’d done y. If you are religious you might try bargaining with God. This is a stage where you try to negotiate yourself out of the situation, which of course is futile. I found myself wondering if I’d picked things up earlier would my son have coped with it better.

Stage four is Depression. I’ve lost count of the number of parents of children with differences who have ended up in a state of depression. That feeling of “can I carry on?” and the strain of holding together a family and marriage often takes its toll. Whether this is clinical depression or a sense of depression – a feeling of emptiness, the effects are often similar. We often feel helpless.

As we come out of the grief cycle, we reach Acceptance. This is where we realise that the world hasn’t ended, life will continue and we can deal with this. I believe it is only when we reach acceptance that we can start to advocate properly for our children with differences. If we are able to accept the reality of what is, we can channel our energies into understanding, and accessing support, rather than denying, bargaining or being angry.

I suspect I went through the grief cycle fairly quickly. I certainly recall googling “successful people with dyslexia” very soon after having read the report. Coming to a place of acceptance can take anything from a few hours to, in some cases years. Some people never really get there, and sadly many failed marriages are a result of this.

So, if you feel like you are suffering a bereavement, you probably are. Give yourself the time and space you deserve and do everything you need to navigate the grief cycle. It’s a natural process we all go through.

One of the positives that have come out of parenting children with differences, is I have become a better and more empathetic parent. I’m more creative, more resilient and far stronger than I would ever have been otherwise.